Science and Exploration

In 1878, the governor-general of Sichuan Province was greatly distressed. Two British explorers, backed by the threat of violence from their government, had just pushed into the territories he administered, feeling their way, town by town, toward the Tibetan, Indian, and Burmese borders, and mapping what he imagined (not incorrectly) might be routes for invading armies. He rushed, therefore, to organize a counter-expedition, instructing it to trail the foreign interlopers, trace what they might know, and reconnoiter the danger he and China faced.

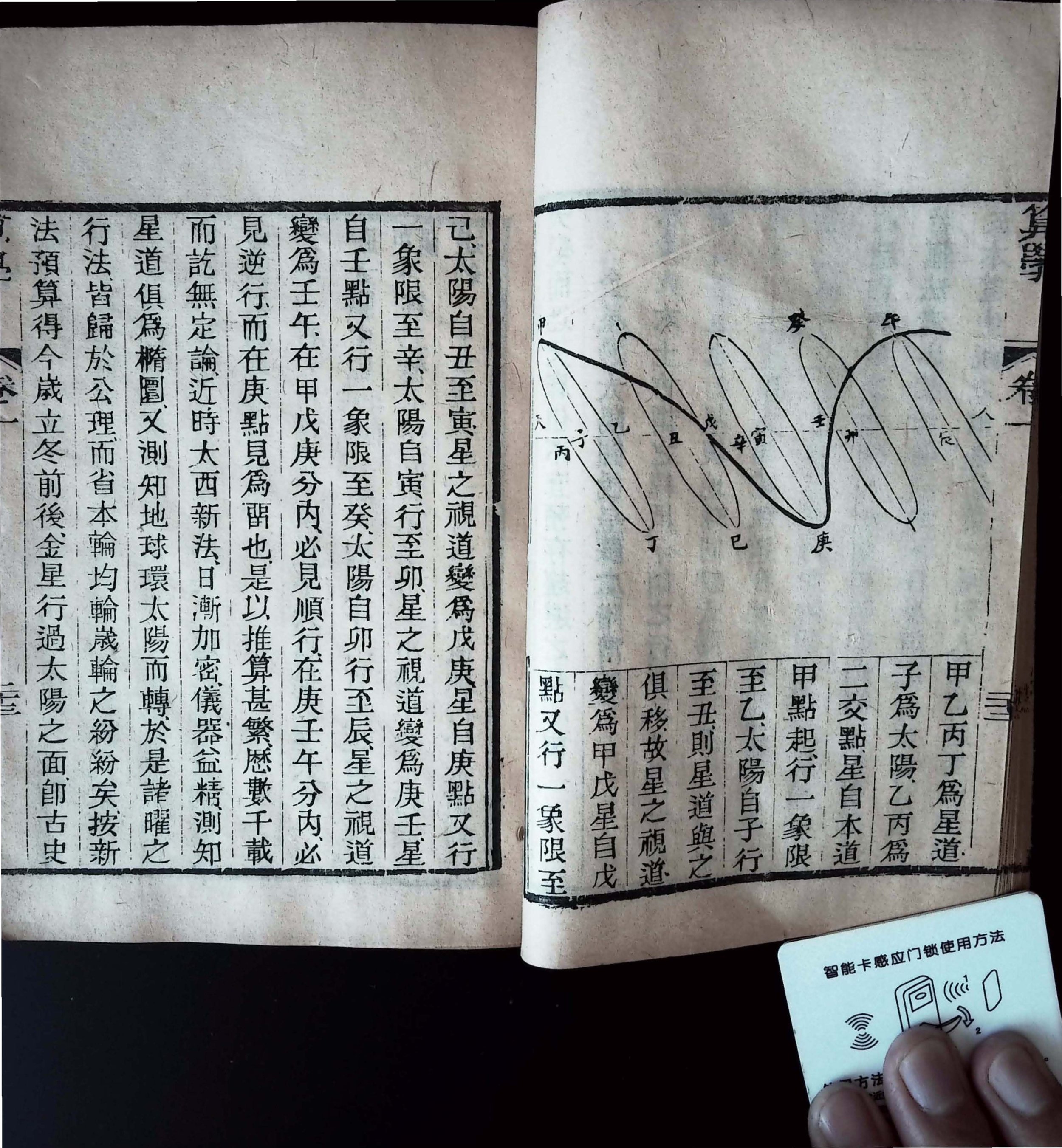

Huang’s Discourse on

Planetary Motion

To lead this Indian expedition—the first in a thousand years—he turned to a radically unlikely figure. Instead of the soldier, or Buddhist monk, or Confucian scholar-official he might have chosen in the past, the governor appointed an amateur scientist to surreptitiously map the Himalayan passes and gather intelligence on the societies beyond the mountains. He chose, in other words, to transform an individual immersed in astronomy, mathematics, and physics into China’s first modern explorer.

How and why did this shift toward a reliance on Western scientific epistemologies occur? Where did this amateur Chinese scientist come from? How did mathematical, natural historical, and technical knowledge shape the emerging world of high imperialism? Examining the life of the late-Qing scientist-explorer Huang Maocai 黃楙材 (1843-1890), my second monograph uncovers the little-known story of China’s nineteenth-century Great Game. Though studying the intersection of science, technology, and geo-politics, the book tells the story of large structural changes in science and politics from below, a social and personal history of the advent of imperialist modernity.